Multi-Language Development¶

Software projects often involve more than one programming language. Typically that's because there is existing code that already does something we need done and, for that specific code, it doesn't make economic sense to redevelop it in some other language. Consider the rotor blade model in a high-fidelity helicopter simulation. Nobody touches the code for that model except for a few specialists, because the code is extraordinarily complex. (This complexity is unavoidable because a rotor blade's dynamic behavior is so complex. You can't even model it as one physical piece because the tip is traveling so much faster than the other end.) Complex and expensive models like that are a simulator company's crown jewels; their cost is meant to be amortized over as many projects as possible. Nobody would imagine redeveloping it simply because a new project is to be written in a different language.

Therefore, Ada includes extensive facilities to "import" foreign entities into Ada code, and to "export" Ada entities to code in foreign languages. The facilities are so useful that Ada has been used purely as "glue code" to allow code written in two other programming languages to be used together.

You've already seen an introduction to Ada and C code working together in the "Interfacing" section of the Ada introductory course. If you have not seen that material, be sure to see it first. We will cover some further details not already discussed there, and then go into the details of the facilities not covered elsewhere, but we assume you're familiar with it.

The Ada foreign language interfacing facilities include both "general" and

"language-specific" capabilities. The "general" facilities are known as such

because they are not tied to any specific language. These pragmas and aspects

work with any of the supported foreign languages. In contrast, the

"language-specific" interfacing facilities are collections of Ada declarations

that provide Ada analogues for specific foreign language types and subprograms.

For example, as you saw in that "Interfacing" section, there is a package with

a number of declarations for C types, such as int, float, and

double, as well as C "strings", with subprograms to convert back and forth

between them and Ada's string type. Other languages are also supported, both by

the Ada Standard and by vendor additions. You will frequently use both the

"general" and the "language-specific" facilities together.

All these interfacing capabilities are defined in Annex B of the language

standard. Note that Annex B is not a "Specialized Needs" annex, unlike some of

the other annexes. The Specialized Needs annexes are wholly optional, whereas

all Ada implementations must implement Annex B. However, some parts of Annex B

are optional, so more precisely we should say that every implementation must

support all the required features of Annex B. That comes down mainly to the

package Interfaces (more on that package in a moment). However, if an

implementation does implement any optional part of Annex B, it must be

implemented as described by the standard, or with less functionality. An

implementation cannot use the same name for some facility (aspect, etc.) but

with different semantics. That's true of the Specialized Needs annexes too:

not every part need be implemented, but any part that is implemented must

conform to the standard. In practice, for Annex B, all implementations provide

the required parts, but not all provide support for all the "language-specific"

foreign languages' interfaces. The vendors make a business decision for the

optional parts, just as they do regarding the Specialized Needs annexes.

General Interfacing¶

In the "Interfacing" section of the Ada introductory course you saw that Ada defines aspects and pragmas for working with foreign languages. These aspects and pragmas are functionally interchangeable, and we will use whichever one of the two that is most convenient in our discussion. The pragmas are officially "obsolescent," but that merely means that a newer approach is available, in this case the corresponding aspects. You can use either one without concern for future support because language constructs that are obsolescent are not removed from the language. Any compiler that supports such constructs will almost certainly support them forever, for the sake of not invalidating existing customers' code. The pragmas have been in the language since Ada 95 so there's a lot of existing code using them. Changing the compiler isn't cost-free, after all, so why spend the money to potentially lose a customer? Likewise, a brand new compiler will also probably support them, for the sake of potentially gaining a customer.

The general interfacing facility consists of these aspects and pragmas,

specifically Import, Export, and Convention. As you saw in

the Ada Introduction course, Import brings a foreign entity into Ada

code, Export does the opposite, and Convention supplies

additional information and directives to the compiler. We will go into the

details of each.

Regardless of whether the Ada code is importing or exporting some entity, there will be an Ada declaration for that entity. That declaration tells the compiler how the entity can be used, as usual. The interfacing aspects and pragmas are then applied to these Ada declarations.

If we are exporting, then the entity is implemented in Ada. For a subprogram

that means there will also be a subprogram body matching the declaration, and

the compiler will enforce that requirement as usual. In contrast, if we are

importing a subprogram, then it is not implemented in Ada, and therefore there

will be no corresponding subprogram body for the Ada declaration. The compiler

would not allow it if we tried. In that case the Import is the

subprogram's completion.

Subprograms often have a separate declaration. Sometimes that's required, for example when we want to include a subprogram as part of a package's API, but at other times it is optional. Remember that a subprogram body acts as a corresponding declaration when there is no separate declaration defined. Thus, either way, we have a subprogram declaration available for the interfacing aspects and/or pragmas.

For data that are imported or exported, we'll have the declaration of the object in Ada to which we can apply the necessary interfacing aspects/pragmas. But we will also have the types for these objects, and as you will see, the types can be part of interfacing too.

Aspect/Pragma Convention¶

As you saw in the

"Interfacing" section of the Ada introductory course,

when importing and exporting you'll also specify the "convention" for the

entity in question. The pragmas for importing and exporting include a parameter

for this purpose. When using the aspects, you'll specify the Convention

aspect too.

For types, though, you will specify the Convention aspect/pragma alone,

without Import or Export. In this case the convention specifies

the layout for objects of that type, presumably a layout different than the Ada

compiler would normally use. You would need to specify this other layout either

because you're going to later declare and export an object of the type, or

because you are going to declare an object of the type and pass it as a

argument to an imported subprogram.

For example, Ada specifies that multi-dimensional arrays are represented in memory in row-major order. In contrast, the Fortran standard specifies column-major order. If we want to define a type in Ada that can be used for passing parameters to Fortran routines, we need to specify that convention for the type. For example:

type Matrix is array (Rows, Columns) of Float

with Convention => Fortran;

(Rows and Columns are user-defined discrete subtypes.)

As a result when we declare Matrix objects the Ada compiler will use the

column-major layout. That makes it possible to pass objects of the type to

imported Fortran subprograms because the formal parameter will also be of type

Matrix. The imported Fortran routine will then see the parameter in

memory as it expects to see it. So although you wouldn't need to import or

export a type itself, you might very well import or export an object of the

type, or pass it as a argument.

When Convention is applied to subprograms, a natural mistake is to think

that we are specifying the programming language used to implement the

subprogram. In reality, the convention indicates the subprogram calling

convention, not the implementation language. The calling convention specifies

how parameters are passed to and from subprogram calls, how result values for

functions are returned, the order that parameters are pushed on the call stack,

how dynamically-sized parameters are passed, and so on. Ordinarily these are

matters you don't need to consider because you're working within a single

convention automatically, in other words the one used by the Ada compiler

you're using.

To illustrate that the convention is not the implementation language, consider

a subprogram that we intend to import and call from Ada. This imported routine

is implemented in assembly language, but, in addition, let's say it is written

to use the same calling convention as the Ada compiler we are using for Ada

code. Therefore, the calling convention would be Ada even though the

implementation is in assembler.

procedure P (X : Integer) with

...

Convention => Ada,

...

In the example above, Ada is known as a convention identifier, as is

Fortran in the earlier example. Convention identifiers are defined by

the Ada language standard, but also by Ada vendors.

The Ada standard defines two convention identifiers: Ada (the default),

and Intrinsic. In addition, Annex B defines convention identifiers

C, COBOL, and Fortran. Support for these Annex B

conventions is optional.

GNAT supports the standard and Annex B conventions, as well as the following:

Assembler, "C_PLUS_PLUS" (or CPP), Stdcall, WIN32,

and a few others. C_PLUS_PLUS is the convention identifier required by

the standard when C++ is supported. (Convention identifiers are actual

identifiers, not strings, so they must obey the syntax rules for identifiers.

"C++" would not be a valid identifier.) See the GNAT User Guide for those other

GNAT-specific conventions.

Stdcall and WIN32 actually do specify a particular calling

convention, but for those convention identifiers that are language names, how

do we get from the name to a calling convention?

The ultimate requirement for any calling convention is compatibility with the Ada compiler we are using. Specifically, the Ada compiler must recognize what the calling convention specifies, and support importing and exporting subprograms with that convention applied.

For the Ada convention that's simple. There is no standard calling

convention for Ada. Convention Ada simply means the calling convention

applied by the Ada compiler we happen to be using. (We'll talk about

Intrinsic shortly.)

So far, so good. But how to we get from those other language names to corresponding calling conventions? There is no standard calling convention for, say, C, any more than there is a standard calling convention for Ada.

In fact we don't get to the calling convention, at least not directly. What the

language name in the convention identifier actually tells us is that, when that

convention is supported, there is a compiler for that foreign language that

uses a calling convention known to, and supported by, the Ada compiler we are

using. The Ada compiler vendor defines which languages it supports, after all.

For example, when supported, convention C means that there is a

compatible C compiler known to the Ada compiler vendor. For GNAT you can guess

which C compiler that might be.

It's actually pretty straightforward once you have the big picture. If the convention is supported, the Ada compiler in use knows of a compiler for that language with which it can work. Annex B just defines some convention identifiers for the sake of portability.

But suppose a given Ada compiler supports more than one vendor for a given

programming language? In that case the Ada compiler would define and support

multiple convention identifiers for the same programming language. Presumably

these identifiers would be differentiated by the compiler vendors' names. Thus

we might have available conventions GNU_Fortran and

Intel_Fortran if both were supported. The Fortran convention

identifier would then indicate the default vendor's compiler.

The Intrinsic calling convention represents subprograms that are

"built in" to the compiler. When such a subprogram is called the compiler

doesn't actually generate the code for an out-of-line call. Instead, the

compiler emits the assembly code — often just a single instruction

— corresponding to the intrinsic subprogram's name. There will be a

separate declaration for the subprogram, but no actual subprogram body

containing a sequence of statements. The compiler just knows what to emit in

place of the call.

For example:

function Shift_Left

(Value : Unsigned_16;

Amount : Natural)

return Unsigned_16

with ..., Convention => Intrinsic;

The effect is much like a subprogram call that is always in-lined, except that there's no body for the subprogram. In this example the compiler simply issues a shift-left instruction in assembly language.

You'll see the Intrinsic convention applied to many language-defined

subprograms. For example:

generic

type Source(<>) is limited private;

type Target(<>) is limited private;

function Ada.Unchecked_Conversion(S : Source) return Target

with ..., Convention => Intrinsic;

Thus when we call an instantiation of Ada.Unchecked_Conversion there is

no actual call made to some subprogram. The compiler just treats the bits of

S as a value of type Target.

Intrinsic subprograms are a good way to access interesting capabilities of the target hardware, without having to write the assembly language yourself (although we will show how to do that, later, directly in Ada). For example, some targets provide an instruction that atomically compares and swaps a value in memory. Ada 2022 just added a standard package for this, but before that we could use the following to access a gcc built-in:

-- Perform an atomic compare and swap: if the current value of

-- Destination.all is Comparand, then write New_Value into Destination.all.

-- Returns an indication of whether the swap took place.

function Sync_Val_Compare_And_Swap_Bool_8

(Destination : access Unsigned_8;

Comparand : Unsigned_8;

New_Value : Unsigned_8)

return Boolean

with Convention => Intrinsic,

...

We would specify additional aspects beyond that of Convention but these

have not yet been discussed. That's what the ellipses indicate in the various

examples above.

Aspect/Pragma Import and Export¶

You've already seen these aspects in the Ada Introduction course, but for

completeness: Import brings a foreign entity into Ada code, and

Export makes an Ada entity available to foreign code. In practice, these

entities consist of objects and subprograms, but the language doesn't impose

many restrictions. It is up to the vendor to decide what makes sense for their

specific target.

The aspects Import and Export are so-called Boolean aspects

because their value is either True or False. For example:

Obj : Matrix with

Export => True,

...

For any Boolean-valued aspect the default is True so you only need to

give the value explicitly if that value is False. There would be no

point in doing that in these two cases, of course. Hence we just give the

aspect name:

Obj : Matrix with

Export,

...

Recall that objects of some types are initialized automatically during the

objects' elaboration, unless they are explicitly initialized as part of their

declarations. Access types are like that, for example. Objects of these types

are default initialized to null as part of ensuring that their values

are always meaningful (absent unchecked conversion).

type Reference is access Integer;

Obj : Reference;

In the above the value of Obj is null, just as if we had

explicitly set it that way.

But that initialization is a problem if we are importing an object of an access type. Presumably the value is set by the foreign code, so automatic initialization to null would overwrite the incoming value. Therefore, the language guarantees that implicit initialization won't be applied to imported objects.

type Reference is access Integer;

Obj : Reference with Import;

Now the value of Obj is whatever the foreign code sets it to, and is

not, in other words, overwritten during elaboration of the declaration.

Aspect/Pragma External_Name and Link_Name¶

For an entity with a True Import or Export aspect, we can

also specify a so-called external name or link name. These names are specified

via aspects External_Name and Link_Name respectively.

An external name is a string value indicating the name for some entity as known by foreign language code. For an entity that Ada code imports, this is the name that the foreign code declares it to be. For an entity that Ada code exports, this is the name that the foreign code is told to use. This string value is exactly the name to be used, so if you misspell the name the link will fail. For example:

function Sync_Val_Compare_And_Swap_Bool_8

(Destination : access Unsigned_8;

Comparand : Unsigned_8;

New_Value : Unsigned_8)

return Boolean

with

Import,

Convention => Intrinsic,

External_Name => "__sync_bool_compare_and_swap_1";

The External_Name and Link_Name values are strings because the

foreign unit names don't necessary follow the Ada rules for identifiers (the

leading underscores in this case). Note that the ending digit in the name above

is different from the declared Ada name.

Usually, the name of the imported or exported entity is precisely known and

hence exactly specified by External_Name. Sometimes, however, a

compilation system may have a linker "preprocessor" that augments the name

actually used by the linkage step. For example, an implementation might always

prepend "_" and then pass the result to the system linker. In that case we

don't want to specify the exact name. Instead, we want to provide the

"starting point" for the name modification. That's the purpose of the

aspect Link_Name.

If you don't specify either External_Name or Link_Name the

compilation system will choose one in some implementation-defined manner.

Typically this would be the entity's defining name in the Ada declaration, or

some simple transformation thereof. But usually we know the name exactly and

so we use External_Name to give it.

As you can see, it really wouldn't make sense to specify both

External_Name and Link_Name since the semantics of the two

conflict. But if both are specified for some reason, the External_Name

value is ignored.

Note that Link_Name cannot be specified for Intrinsic subprograms

because there is no actual unit being linked into the executable, because

intrinsics are built-in. In this case you must specify the

External_Name.

Finally, because you will see a lot the pragma usage we should go into enough detail so that you know what you're looking at when you see them.

Pragma Import and pragma Export work almost like a subprogram

call. Parameters cannot be omitted unless named notation is used. Reordering

the parameters is not permitted, however, unlike subprogram calls.

The BNF syntax is as follows. We show Import, but Export has identical parameters:

pragma Import(

[Convention =>] convention_identifier,

[Entity =>] local_name

[, [External_Name =>] external_name_string_expression]

[, [Link_Name =>] link_name_string_expression]);

As you can see, the parameters correspond to the individual aspects

Convention, External_Name, and Link_Name. When using

aspects you don't need to say which Ada entity you're applying the aspects to,

because the aspects are part of the entity declaration syntax. In contrast,

the pragma is distinct from the declaration so we must specify what's being

imported or exported via the Entity parameter. That's the declared Ada

name, in other words. Note that both the External_Name and

Link_Name parameters are optional.

Here's that same built-in function, using the pragma to import it:

-- Perform an atomic compare and swap: if the current value of

-- Destination.all is Comparand, then write New_Value into Destination.all.

-- Returns an indication of whether the swap took place.

function Sync_Val_Compare_And_Swap_Bool_8

(Destination : access Unsigned_8;

Comparand : Unsigned_8;

New_Value : Unsigned_8)

return Boolean;

pragma Import (Intrinsic,

Sync_Val_Compare_And_Swap_Bool_8,

"__sync_bool_compare_and_swap_1");

The first pragma parameter is for the convention. The next parameter, the

Entity, is the Ada unit's declared name. The last parameter is the

external name. The compiler either knows what we are referencing by that

external name or it will reject the pragma. As we mentioned before, the string

value for the name is not required to match the Ada unit name.

You will see later that there are other convention identifiers as well, but we will wait for the Specific Interfacing section to introduce those.

Package Interfaces¶

Package Interfaces must be provided by all Ada implementations. The

package is intended to provide types that reflect the actual numeric types

provided by the target hardware. Of course, the standard has no way to know

what hardware is involved, therefore the actual content is

implementation-defined. But even so, it is possible to standardize the names for

these types, and that is what the language standard does.

Specifically, the standard defines the format for the names for the hardware's signed and modular (unsigned) integer types, and for the floating-point types.

The signed integers have names of the form Integer_n, where n is the

number of bits used by the machine-supported type. The type for an eight-bit

signed integer would be named Integer_8, for example, and then

Integer_16 and so on for the larger types, for as many as the target

machine supports.

Likewise, for the unsigned integers, the names are of the form

Unsigned_n, with the same meaning for n. The colloquial eight-bit

"byte" would be named Unsigned_8, with Unsigned_16 for the 16-bit

version, and so on, again for as many as the machine supports.

For floating-point types it is harder to talk about a format that is

sufficiently common to standardize. The IEEE floating-point standard is well

known and widely used, however, so if the machine does support the IEEE format

that name can be used. Such types would be named IEEE_Float_n, again

with the same meaning for n. Thus we might see declarations for types

IEEE_Float_32 and IEEE_Float_64 and so on, for all the machine

supported floating-point types.

In addition to these type declarations, for the unsigned integers only, there will be declarations for shift and rotate operations provided as intrinsic functions.

The resulting package declaration might look something like this:

package Interfaces is

type Integer_8 is range -2 ** 7 .. 2 ** 7 - 1;

type Integer_16 is range -2 ** 15 .. 2 ** 15 - 1;

type Integer_32 is range -2 ** 31 .. 2 ** 31 - 1;

...

type Unsigned_8 is mod 2 ** 8;

function Shift_Left (Value : Unsigned_8; Amount : Natural) return Unsigned_8;

function Shift_Right (Value : Unsigned_8; Amount : Natural) return Unsigned_8;

function Rotate_Left (Value : Unsigned_8; Amount : Natural) return Unsigned_8;

function Rotate_Right (Value : Unsigned_8; Amount : Natural) return Unsigned_8;

function Shift_Right_Arithmetic (Value : Unsigned_8; Amount : Natural)

return Unsigned_8;

type Unsigned_16 is mod 2 ** 16;

function Shift_Left (Value : Unsigned_16; Amount : Natural)

return Unsigned_16;

function Shift_Right (Value : Unsigned_16; Amount : Natural)

return Unsigned_16;

...

type Unsigned_32 is mod 2 ** 32;

function Shift_Left (Value : Unsigned_32; Amount : Natural)

return Unsigned_32;

function Shift_Right (Value : Unsigned_32; Amount : Natural)

return Unsigned_32;

...

type IEEE_Float_32 is digits 6;

type IEEE_Float_64 is digits 15;

...

end Interfaces;

As you can see, when you need to write code in terms of the hardware's numeric

types, this package is a great resource. There's no need to declare your own

UInt32 type, for example, although of course you could, trivially:

type UInt32 is mod 2 ** 32;

But if you do, realize that you won't get the shift and rotate operations for

your type. Those are only defined for the types in package Interfaces.

If you do need to declare such a type, and you do want the additional

shift/rotate operations, use inheritance:

type UInt32 is new Interfaces.Unsigned_32;

GNAT also defines a pragma, as an alternative to inheritance:

type UInt32 is mod 2 ** 32;

pragma Provide_Shift_Operators (UInt32);

The approach using inheritance is preferable because it is portable, all other things being equal.

One reason to make up your own unsigned type is that you need one that does not

in fact reflect the target hardware's numeric types. For example, a hardware

device register might have gaps of bits that are currently not used by the

device. Those gaps are frequently not the size of a type declared in package

Interfaces. We might need an Unsigned_3 type, for example. That's

a reasonable thing to do.

Language-Specific Interfacing¶

In addition to the aspects and pragmas for importing and exporting entities that work with any language, Ada also defines standard language-specific facilities for interfacing with a set of foreign languages. The standard defines which languages, but vendors can (and do) expand the set.

Specifically, the "language-specific" interfacing facilities are collections of

Ada declarations that provide Ada analogues for specific foreign language types

and subprograms. Package Interfaces is the root package for a hierarchy

of packages that organize these declarations by language, with one or more

child packages per language.

Note that the declarations within package Interfaces are, by definition,

compile-time visible to any child package in the subsystem. Thus whenever one

of the language-specific packages needs to mention the machine types they are

automatically available.

The standard defines specific support for foreign languages C, COBOL, and

Fortran. Thus there are one or more child packages rooted at Interfaces

that have those language names as their child package names:

Interfaces.C, Interfaces.COBOL, and Interfaces.Fortran.

The material below will focus on C and, to a lesser extent, Fortran, ignoring altogether the support for COBOL. That's not because COBOL is unimportant. There is a lot of COBOL business software out there in use. Rather, we skip COBOL because it is not relevant to embedded systems. Similarly, although Fortran is extensively used, especially in high-performance computing, it is not used extensively in embedded systems. We will provide some information about the Fortran support but will not dwell on it.

Even though we do not consider C to be appropriate for large development projects, neither technically not economically, it has its place in small, low-criticality embedded systems. Ada developers can profit from existing device drivers and mature libraries coded in C, for example. Hence interfacing to it is important.

What about C++? Interfacing to C++ is tricky compared to C, because of the

vendor-defined name-mangling, automatic invocations of constructors and

destructors, exceptions, and so on. Generally, interfacing with C++ code can

be facilitated by preventing much of those difficulties using the

extern "C" {... } linkage-specification. Doing so then makes the

bracketed C++ code look like C, so the C interfacing facilities then can be

used.

Package Interfaces.C¶

The child package Interfaces.C supports interfacing with units written

in the C programming language. Support is in the form of Ada constants and

types, and some subprograms. The constants correspond to C's limits.h

header file, and the Ada types correspond to types for C's int,

short, unsigned_short, unsigned_long,

unsigned_char, size_t, and so on. There is also support for

converting Ada's type String to/from char_array, and similarly

for type Wide_String, etc.

It's a large package so we will elide parts. The idea is to give you a feel for what's there. If you want the details, see either the Ada reference manual or bring up the source code in GNAT Studio.

package Interfaces.C is

-- Declaration's based on C's <limits.h>

CHAR_BIT : constant := 8;

SCHAR_MIN : constant := -128;

SCHAR_MAX : constant := 127;

UCHAR_MAX : constant := 255;

-- Signed and Unsigned Integers. Note that in GNAT, we have ensured that

-- the standard predefined Ada types correspond to the standard C types

type int is new Integer;

type short is new Short_Integer;

type long is range -(2 ** (System.Parameters.long_bits - Integer'(1)))

.. +(2 ** (System.Parameters.long_bits - Integer'(1))) - 1;

type long_long is new Long_Long_Integer;

type signed_char is range SCHAR_MIN .. SCHAR_MAX;

for signed_char'Size use CHAR_BIT;

type unsigned is mod 2 ** int'Size;

type unsigned_short is mod 2 ** short'Size;

type unsigned_long is mod 2 ** long'Size;

type unsigned_long_long is mod 2 ** long_long'Size;

...

-- Floating-Point

type C_float is new Float;

type double is new Standard.Long_Float;

type long_double is new Standard.Long_Long_Float;

----------------------------

-- Characters and Strings --

----------------------------

type char is new Character;

nul : constant char := char'First;

function To_C (Item : Character) return char;

function To_Ada (Item : char) return Character;

type char_array is array (size_t range <>) of aliased char;

for char_array'Component_Size use CHAR_BIT;

...

end Interfaces.C;

The primary purpose of these types is for use in the formal parameters of Ada subprograms imported from C or exported to C. The various conversion functions can be called from within Ada to manipulate the actual parameters.

When writing the Ada subprogram declaration corresponding to a C function, an Ada procedure directly corresponds to a void function. An Ada procedure also corresponds to a C function if the return value is always to be ignored. Otherwise, the Ada declaration should be a function.

As we said, the types declared in this package can be used as the formal

parameter types. That is the intended and recommended approach. However, some

Ada types naturally correspond to C types, and you might see them used instead

of those from Interfaces.C. Type int is the C native integer type

for the target, for example, as is type Integer in Ada. Likewise, C's

type float and type Ada's Float are likely compatible. GNAT goes

to some lengths to maintain compatibility with C, since the two gcc compilers

share so much internal technology. Other vendors might not do so. Best practice

is use the types in Interfaces.C for your parameters.

Of course, the types in Interfaces.C are not sufficient for all uses.

You will often need to use user-defined types for the formal parameters, such

as enumeration types and record types.

Ada enumeration types are compatible with C's enums but note that C requires

enum values to be the size of an int, whereas Ada does not. The Ada

compiler uses whatever sized machine type will support the specified number of

enumeral values. It might therefore be smaller than an int but it might

also be larger. (Declaring more enumeration values than would fit in an integer

is unlikely except in tool-generated code, but it is possible.) For example:

type Small_Enum is (A, B, C);

If we printed the object size for Small_Enum we'd get 8 (on a typical

machine with GNAT). Therefore, applying the aspect Convention to the Ada

enumeration type declaration is a good idea:

type Small_Enum is (A, B, C) with Convention => C;

Now the object size will be 32, the same as int.

Speaking of enumeration types, note that Ada 2022 added a boolean type to

Interfaces.C named C_Bool to match that of C99, so you should use

it instead of Ada's Boolean type for formal parameters.

A simple Ada record type is compatible with a C struct, but remember that the Ada compiler is allowed to reorder the record components. The compiler would do that if it saw that the layout was inefficient, but the point here is that the compiler could do it silently. As a result, you should specify the record layout explicitly using a record representation clause, matching the layout of the C struct in question. Then there will be no question of the layouts matching. Once your record types get more complicated, for example with discriminants or tagged record extensions, things get tricky. Your best bet it to stick with the simple cases when interfacing to C.

Some types that you might think would correspond do not, at least not

necessarily. For example, an Ada access type's value might be represented as a

simple address, but it might not. In GNAT, an access value designating a value

of some unconstrained array type (e.g., String) is comprised of two

addresses, by default. One designates the characters and the other designates

the bounds. You can override that with a pragma, but you must know to do so.

For example, if we run the following program, we will see that the object size

for the access type Name is twice the object size of

System.Address:

with Ada.Text_IO; use Ada.Text_IO;

with System; use System;

procedure Demo is

type Name is access String;

begin

Put_Line (Address'Object_Size'Image);

Put_Line (Name'Object_Size'Image);

end Demo;

Some Ada types simply have no corresponding type in C, such as record extensions, task types, and protected types. You'll have to pass those as an "opaque" type, usually as an address. It isn't clear that a C function would know what to do with values of these types, but the general notion of passing an opaque type as an address is useful and not uncommon. Of course, that approach forgoes all type safety, so avoid it when possible.

In addition to the types for the formal parameters, you'll also need to know

how parameters are passed to and from C functions. That affects the parameter

profiles on both sides, Ada and C. The text in Annex B for Interfaces.C

specifies how parameters are to be passed back and forth between Ada and C so

that your subprogram declarations can be portable. That's the approach for each

supported programming language, i.e., in the discussion of the corresponding

child package under Interfaces.

The rules are expressed in terms of scalar types, "elementary" types, array types, and record types. Remember that scalar types are composed of the discrete types and the real types, so we're talking about the signed and modular integers, enumerations, floating-point, and the two kinds of fixed-point types. The "elementary" types consist of the scalars and access types. The rules are fairly intuitive, but throw in Ada's access parameters and parameter modes and some subtleties arise. We won't cover all the various rules but will explore some of the subtleties.

First, the easy cases: mode in scalar parameters, such as int,

as simply passed by copy. Scalar parameters are passed by copy anyway in Ada so

the mechanism aligns with C in a straightforward manner. A record type T

is passed by reference, so on the C side we'd see t* where t is a C

struct corresponding to T. A constrained array type in Ada with a

component type T would correspond to a C formal parameter t* where

t corresponds to T. An Ada access parameter access T

corresponds on the C side to t* where t corresponds to T. And

finally, a private type is passed according to the full definition of the type;

the fact that it is private is just a matter of controlling the client

view, being private doesn't affect how it is passed. There are other simple

cases, such as access-to-subprogram types, but we can leave that to the Annex.

Now to the more complicated cases. First, some C ABIs (application binary

interfaces) pass small structs by copy instead of by reference. That can make

sense, in particular when the struct is small, say the size of an address or

smaller. In that case there's no performance benefit to be had by passing a

reference. When that situation applies, there is another convention we have

not yet mentioned: C_Pass_By_Copy. As a result the record parameter

will be passed by copy instead of the default, by reference (i.e., T

rather than *T), as long as the mode is in. For example:

type R2 is record

V : int;

end record

with Convention => C_Pass_By_Copy;

procedure F2 (P : R2) with

Import,

Convention => C,

External_Name => "f2";

struct R2 {

int V;

};

void f2 (R2 p);

On the C side we expect that p is passed by copy and indeed that is how we

find it. That said, passing record values to structs by reference is the more

common programmer choice. Like arrays, records are typically larger than an

address. The point here is that the Ada code can be configured easily to match

the C code.

Next, consider passing array values, both to and from C. When passing an array value to C, remember that Ada array types have bounds. Those bounds are either specified at compile time when they are declared, or, for unconstrained array types, specified elsewhere, at run-time.

Array types are not first-class types in C, and C has no notion of unconstrained array types, or even of upper bounds. Therefore, passing an unconstrained array type value is interesting. One approach is to avoid them. Instead, declare a sufficiently large constrained array as a subtype of the unconstrained array type, and then just pass the actual upper bound you want, along with the array object itself.

type List is array (Integer range <>) of Interfaces.C.int;

subtype Constrained_List is List (1 .. 100);

procedure P (V : Constrained_List; Size : Interfaces.C.int);

pragma Import (C, P, "p");

Obj : Constrained_List := (others => 42); -- arbitrary values

With that, we can just pass the value by reference as usual on the C side:

void p (int* v, int size) {

// whatever

}

But that's assuming we know how many array components are sufficient from the C

code's point of view. In the example above we'll pass a value up to 100 to the

Size parameter and hope that is sufficient.

Really, it would work to use the unconstrained array type as the formal parameter type instead:

type List is array (Integer range <>) of Interfaces.C.int;

procedure P (V : List; Size : Interfaces.C.int);

pragma Import (C, P, "p");

The C function parameter profile wouldn't change. But why does this work? With values of unconstrained array types, the bounds are stored with the value. Typically they are stored just ahead of the first component, but it is implementation-defined. So why doesn't the above accidentally pass the bounds instead of the first array component itself? It works because we are guaranteed by the Ada language that passing an array will pass (the address of) the components, not the bounds, even for Ada unconstrained array types.

Now for the other direction: passing an array from C to Ada. Here the lack of bounds information on the C side really makes a difference. We can't just pass the array by itself because that would not include the bounds, unlike an Ada call to an Ada routine. In this case the approach is the similar to the first alternative described above, in which we declare a very large array and then pass the bounds explicitly:

type List is array (Natural) of int;

-- DO NOT DECLARE AN OBJECT OF THIS TYPE

procedure P (V : List; Size : Interfaces.C.int);

pragma Export (C, P, "p");

procedure P (V : List; Size : Interfaces.C.int) is

begin

for J in 0 .. Size - 1 loop

-- whatever

end loop;

end P;

extern void p (int* v, int size);

int x [100];

p (x, 100); // call to Ada routine, passing x

The fundamental idea is to declare an Ada type big enough to handle anything

conceivably needed on the C side. Subtype Natural means

0 .. Integer'Last so List is quite large indeed. Just be sure

never to declare an object of that type. You'll probably run out of storage on

an embedded target.

Earlier we said that it is the Ada type that determines how parameters are

passed, and that scalars and elementary types are always passed by copy. For

mode in that's simple, the copy to the C formal parameter is done and

that's all there is to it. But suppose the mode is instead out or

in out? In that case the presumably updated value must be returned to

the caller, but C doesn't do that by copy. Here the compiler will come to the

rescue and make it work, transparently. Specifically, we just declare the Ada

subprogram's formal parameter type as usual, but on the C formal we use a

reference. We're talking about scalar and elementary types so let's use

int arbitrarily. We make the mode in out but out would

also serve:

procedure P (Formal : in out int);

void function p (int* formal);

Now the compiler does its magic: it generates code to make a copy of the actual parameter, but it makes that copy into a hidden temporary object. Then, when calling the C routine, it passes the address of the hidden object, which corresponds to the reference expected on the C side. The C code updates the value of the temporary object via the reference, and then, on return, the compiler copies the value back from the temporary to the actual parameter. Problem solved, if a bit circuitous.

There are other aspects to interfacing with C, such as variadic functions that take a varying number of arguments, but you can find these elsewhere in the learn courses.

Next, we examine the child packages under Interfaces.C. These packages

are not used as much as the parent Interfaces.C package so we will

provide an overview. You can look up the contents within GNAT Studio or the Ada

language standard.

Package Interfaces.C.Strings¶

Package Interfaces.C declares types and subprograms allowing an Ada

program to allocate, reference, update, and free C-style strings. In

particular, the private type chars_ptr corresponds to a common use of

char * in C programs, and an object of this type can be passed to

imported subprograms for which char * is the type of the argument of the

C function. A subset of the package content is as follows:

package Interfaces.C.Strings is

type chars_ptr is private;

...

function New_Char_Array (Chars : in char_array) return chars_ptr;

function New_String (Str : in String) return chars_ptr;

procedure Free (Item : in out chars_ptr);

...

function Value (Item : in chars_ptr) return char_array;

function Value (Item : in chars_ptr) return String;

...

function Strlen (Item : in chars_ptr) return size_t;

procedure Update (Item : in chars_ptr;

Offset : in size_t;

Chars : in char_array;

Check : in Boolean := True);

...

end Interfaces.C.Strings;

Note that allocation might be via malloc, or via Ada’s allocator new. In

either case, the returned value is guaranteed to be compatible with

char*. Deallocation must be via the supplied procedure Free.

An amusing point is that you can overwrite the end of the char array just like

you can in C, via procedure Update. The Check parameter indicates

whether overwriting past the end is checked. The default is True, unlike

in C, but you could pass an explicit False if you felt the need to do

something questionable.

Package Interfaces.C.Pointers¶

The generic package Interfaces.C.Pointers allows us to perform C-style

operations on pointers. It includes an access type named Pointer,

various Value functions that dereference a Pointer value and

deliver the designated array, several pointer arithmetic operations, and "copy"

procedures that copy the contents of a source pointer into the array designated

by a destination pointer.

We won't go into the details further. See the Ada RM for more.

Package Interfaces.Fortran¶

Like Interfaces.C, package Interfaces.Fortran defines Ada types to be

used when working with subprograms using the Fortran calling convention. These

types have representations that are identical to the default representations of

the Fortran intrinsic types Integer, Real, Double Precision, Complex,

Logical, and Character in some supported Fortran implementation. And like

the C package, the ways that parameters of various types are passed are also

specified.

We leave the details to you to look up in the language standard, if you find them needed in an embedded application.

Machine Code Insertions (MCI)¶

When working close to the hardware, especially when interacting with a device, it is not uncommon for the hardware to require a very specific set of assembly language instructions to be generated. There are two ways to achieve this: the right way and the wrong way.

The wrong way is to experiment with the source code and compiler switches until you get the exact assembly code you need generated (assuming it is possible at all). But what happens when the next compiler release arrives with a new optimization? And abandon all hope if you go to a new compiler vendor. This approach is both labor-intensive and very brittle.

The right way is to express the precise assembly code sequence explicitly within the Ada source code. (That's true to any high level language, not just Ada.) Or you can call an intrinsic function, if there is one that does exactly what you need. We will focus on inserting it directly, in what is known as "machine code insertion", or "inline assembler."

As an example of the need for this capability, consider the GPIO (General Purpose I/O) port on an STM32 Arm microcontroller. Each port contains 16 individual I/O pins, each of which can be configured as an independent discrete input or output, or as a control line for a device, with pull-up or pull-down registers, with different clock speeds, and so on. Different on-chip devices use various collections of pins in ways specific to the devices, and require exclusive assignment of the pins. However, any given pin can be used by several different devices. For example, pin 11 on port A ("PA11") can be used by USART #1 as the clear-to-send ("CTS") line, or the CAN #1 bus Rx line, or Channel 4 of Timer 1, among others. Therefore, one of the responsibilities of the system designer is to allocate pins to devices, ensuring that they are allocated uniquely. It is difficult to debug the case in which a pin is accidentally configured for one device and then reconfigured for use with another device (assuming the first device remains in use). To help ensure exclusive allocations, every GPIO port on this Arm implementation has a way of locking the configuration of each I/O pin. That way, some other part of the software can't successfully change the configuration accidentally, for use with some other device. Even if the same configuration was to be used for another device, the lock prevents the accidental update so we find out about the unintentional sharing.

To lock a pin on a port requires a special sequence of reads and writes to a GPIO register for that port. A specific bit pattern is required during the reads and writes. The sequence and bit pattern is such that accidentally locking the pin is highly unlikely.

Once we see how to express assembly language sequences in general we will see how to get the necessary sequence to lock a port/pin pair. Unfortunately, although you can express exactly the code sequence required, such a sequence of assembly language instructions is clearly target hardware-specific. That means portability is inherently limited. Moreover, the syntax for expressing it varies with the vendor, even for the same target hardware. Being able to insert it at the Ada source level doesn't help with either portability issue. You should understand that the use-case for machine code insertion is for small, short sequences. Otherwise you would write the code in assembly language directly, in a separate file. That might obtain a degree of vendor independence, at least for the given target, but not necessarily. The use of inline assembler is intended for cases in which a separate file containing assembly language is not simpler.

With those caveats in place, let's first examine how to do it in general and then how to express it with GNAT specifically.

The right way to express an arbitrary sequence of one or more assembly language

statements is to use so-called "code statements." A code statement is an Ada

statement, but it is also a qualified expression of a type defined in package

System.Machine_Code. The content of that package, and the details of

code statements, are implementation-defined. Although that affects portability

there really is no alternative because we are talking about machine instruction

sets, which vary considerably and cannot be standardized at this level.

Package System.Machine_Code contains types whose values provide a way of

expressing assembly instructions. For example, let's say that there is a "HLT"

instruction that halts the processor for some target. There is no other

parameter required, just that op-code. Let's also say that one of the types in

System.Machine_Code is for these "short" instructions consisting only of

an op-code. The syntax for the type declaration would then allow the following

code statement:

Short_Instruction'(Command => HLT);

Each of Short_Instruction, Command, and HLT are defined by

the vendor in this hypothetical version of package System.Machine_Code.

You can see why we say that it is both a statement (note the semicolon) and a

qualified expression (note the apostrophe).

Code statements must appear in a subprogram body, after the begin. Only

code statements are allowed in such a body, only use-clauses can be in the

declarative part, and no exception handlers are allowed. The complete example

would be as follows:

procedure Halt -- stops processor

with Inline;

with System.Machine_Code; use System.Machine_Code;

procedure Halt is

begin

Short_Instruction'(Command => HLT);

end Halt;

With that, to halt the processor the Ada code can simply call procedure

Halt. When the optimizer is enabled there will be no code emitted to

make the call, we'd simply see the halt instruction emitted directly in-line.

Package System.Machine_Code provides access to machine instructions but

as we mentioned, the content is vendor-defined. In addition, the package itself

is optional, but is required if Annex C, the Systems Programming Annex, is

implemented by the vendor. In practice most all vendors provide this annex.

In GNAT, the content of System.Machine_Code looks something like this:

type Asm_Input_Operand is ...

type Asm_Output_Operand is ...

type Asm_Input_Operand_List is array (Integer range <>) of Asm_Input_Operand;

type Asm_Output_Operand_List is array (Integer range <>) of Asm_Output_Operand;

type Asm_Insn is private;

...

function Asm

(Template : String;

Outputs : Asm_Output_Operand := No_Output_Operands;

Inputs : Asm_Input_Operand := No_Input_Operands;

Clobber : String := "";

Volatile : Boolean := False) return Asm_Insn;

With this package content, the expression in a code statement is of type

Asm_Insn, short for "assembly instruction." Multiple overloaded functions named

Asm return values of that type.

The Template parameter in a string containing one or more assembly

language instructions. These instructions are specific to the target machine.

The parameter Outputs provides mappings from registers to source-level

entities that are updated by the assembly statement(s). Inputs provides

mappings from source-level entities to registers for inputs. Volatile,

when True, tells the compiler not to optimize the call away, and Clobber

tells the compiler which registers, or memory, if any, are altered by the

instructions in Template. ("Clobber" is colloquial English for

"destroy.") That last is important because the compiler was likely already

using some of those registers so the compiler will need to restore them after

the call.

We could say, for example, the following, taking all the defaults except for

Volatile:

Asm ("nop", Volatile => True);

As you can imagine the full details are extensive, beyond the scope of this introduction. See the GNAT User Guide ("Inline Assembler") for all the gory details.

Now, back to our GPIO port/bin locking example. The port type is declared as follows:

type GPIO_Port is limited record

...

LCKR : Word with Atomic; -- lock register

...

end record with ...

We've elided all but the LCKR component representing the "lock register"

within each port. We'd have a record representation clause to ensure the

required layout but that's not important here. Word is an unsigned

(modular) 32-bit integer type. One of the hardware requirements for accessing

the lock register is that the entire register has to be read or written

whenever any bits within it are accessed. The compiler must not, for example,

write one of the bytes within the register in order to set or clear a bit

within that part of the register. Therefore we mark the register as Atomic. If

the compiler cannot honor that aspect the compilation will fail, so we would

know there is a problem.

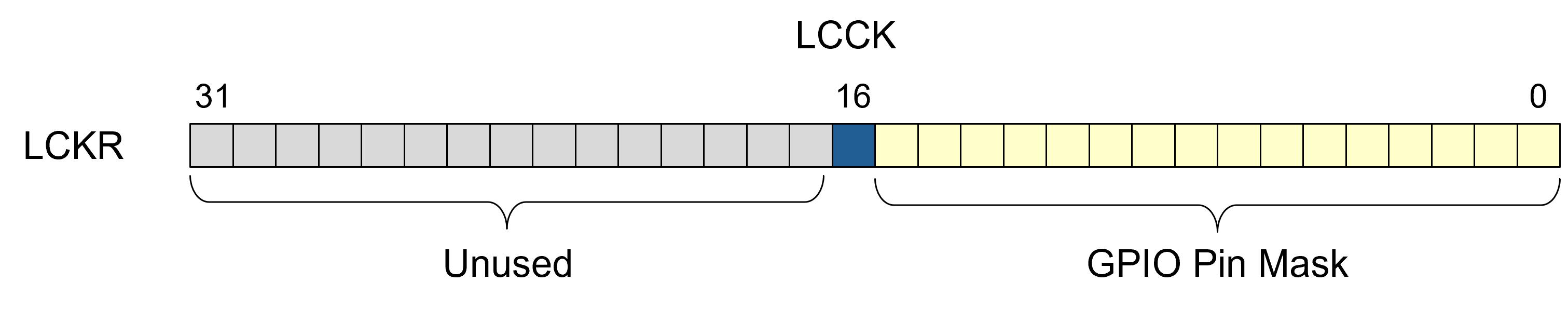

Per the ST Micro Reference Manual, the lock control bit is referred to as

LCKK and is bit #16, i.e., the first in the upper half of the

LCKR register word.

LCCK : constant Word := 16#0001_0000#; -- the "lock control bit"

That bit is also known as the "Lock Key" (hence the abbreviation) because it is used to control the locking of port/pin configurations.

There are 16 GPIO pins per port, represented by the lower 16 bits of the register. Each one of these 16 bits corresponds to one of the 16 GPIO pins on a port. If any given bit reads as a 1 then the corresponding pin is locked.

Graphically that looks like this:

Therefore, the Ada types are:

type GPIO_Pin is

(Pin_0, Pin_1, Pin_2, Pin_3, Pin_4, Pin_5, Pin_6, Pin_7,

Pin_8, Pin_9, Pin_10, Pin_11, Pin_12, Pin_13, Pin_14, Pin_15);

for GPIO_Pin use (Pin_0 => 16#0001#,

Pin_1 => 16#0002#,

Pin_2 => 16#0004#,

...

Pin_15 => 16#8000#);

Note that we had to override the default enumeration representation so that each pin — each enumeral value — would occupy a single dedicated bit in the bit-mask.

With that in place, let's lock a pin. A specific sequence is required to set a pin's lock bit. The sequence writes and reads values from the port's LCKR register. Remember that this 32-bit register has 16 bits for the pin mask (0 .. 15), with bit #16 used as the "lock control bit".

write a 1 to the lock control bit with a 1 in the pin bit mask for the pin to be locked

write a 0 to the lock control bit with a 1 in the pin bit mask for the pin to be locked

do step 1 again

read the entire LCKR register

read the entire LCKR register again (optional)

Throughout the sequence the same value for the lower 16 bits of the word must be maintained (i.e., the pin mask), including when clearing the LCCK bit in the upper half.

If we wrote this in Ada it would look like this:

procedure Lock (Port : in out GPIO_Port; Pin : GPIO_Pin) is

Temp : Word with Volatile;

begin

-- set the lock control bit and the pin bit, clear the others

Temp := LCCK or Pin'Enum_Rep;

-- write the lock and pin bits

Port.LCKR := Temp;

-- clear the lock bit in the upper half

Port.LCKR := Pin'Enum_Rep;

-- write the lock bit again

Port.LCKR := Temp;

-- read the lock bit

Temp := Port.LCKR;

-- read the lock bit again

Temp := Port.LCKR;

end Lock;

Pin'Enum_Rep gives us the underlying value for the enumeration value. We

cannot use 'Pos because that attribute provides the logical position

number within the enumerated values, and as such always increases

consecutively. We need the underlying representation value that we specified

explicitly.

The Ada procedure works, but only if the optimizer is enabled (which also precludes debugging). But even so, there is no guarantee that the required assembly language instruction sequence would be generated, especially one that maintains that required bit mask value on each access. A machine-code insertion is appropriate for all the reasons presented earlier:

procedure Lock (Port : in out GPIO_Port;

Pin : GPIO_Pin) is

use System.Machine_Code, ASCII, System;

begin

Asm ("orr r3, %1, #65536" & LF & HT & -- 0) Temp := LCCK or Pin'Enum_Rep

"str r3, [%0, #28]" & LF & HT & -- 1) Port.LCKR := Temp

"str %1, [%0, #28]" & LF & HT & -- 2) Port.LCKR := Pin'Enum_Rep

"str r3, [%0, #28]" & LF & HT & -- 3) Port.LCKR := Temp

"ldr r3, [%0, #28]" & LF & HT & -- 4) Temp := Port.LCKR

"ldr r3, [%0, #28]" & LF & HT, -- 5) Temp := Port.LCKR

Inputs => (Address'Asm_Input ("r", This'Address), -- %0

(GPIO_Pin'Asm_Input ("r", Pin))), -- %1

Volatile => True,

Clobber => ("r3"));

end Lock;

We've combined the instructions into one Asm expression. As a result, we

can use ASCII line-feed and horizontal tab characters to format the listing

produced by the compiler so that each instruction is on a separate line and

aligned with the previous instruction, as if we had written the sequence in

assembly language directly. That enhances readability later, during examination

of the compiler output to verify the required sequence was emitted.

In the above, "%0" is the first input, containing the address of the

Port parameter. "%1" is the other input, the value of the

Pin parameter. We're using register r3 explicitly, as the

"temporary" variable, so we tell the compiler that it has been "clobbered."

If we examine the assembly language output from compiling the file, we find the

body of procedure Lock is as hoped:

ldr r2, [r0, #4]

ldrh r1, [r0, #8]

.syntax unified

orr r3, r1, #65536

str r3, [r2, #28]

str r1, [r2, #28]

str r3, [r2, #28]

ldr r3, [r2, #28]

ldr r3, [r2, #28]

The first two statements load register 2 (r2) and register 1 (r1) with the subprogram parameters, i.e., the port and pin, respectively. Register 2 gets the starting address of the port record, in particular. (Offset #28 is the location of the LCKR register. The port is passed by reference so that address is actually that of the hardware device.)

We will have separately declared procedure Lock with inlining enabled,

so whenever we call the procedure we will get the exact assembly language

sequence required to lock the indicated pin on the given port, without any

additional code for a procedure call.

Note that we get the calling convention right automatically, because the

subprogram is not a foreign entity written in some other language (such as

assembly language). It's an Ada subprogram with special content so the

Ada convention applies as usual.

When Ada Is Not the Main Language¶

When multiple programming languages are involved, the main procedure might not be implemented in Ada. Maybe the bulk of the program is written in C, for example, and this C code calls some Ada routines that have been exported (with the C convention).

That means the Ada builder does not create the executable image's entry point.

In fact the Ada main procedure is never the entry point for the final

executable image, it's just where the application code begins, like the C

main function. There are setup and initialization steps that must happen

before any program can execute on a target, and the entry point code is

responsible for this functionality. For example, on a bare machine target, the

hardware must be initialized, the trap vectors installed, the segments

initialized, and so on. On a target running an operating system, the OS is

responsible for that initialization but there will be OS-specific

initialization steps too. For example, if command-line arguments are supported

these may be gathered. All this initialization code is generated by the

builder, regardless of the language, followed by a call to the main routine.

Some of the initialization is specific to Ada programming, and must occur before any calls occur to the exported Ada routines. In particular, the entry point code emitted by the Ada builder initializes the Ada run-time system and calls all the elaboration routines for the library units in the application code. Only then does the emitted code invoke the Ada main. If the Ada builder is not going to create the executable it has no chance to emit the code to do that prior initialization. A foreign language builder will not emit such code, so we have a problem.

You could learn enough about how the foreign builder works, and how your Ada builder works, to create a work-around. You could learn what the Ada builder would emit, in other words, and ensure those routines are called manually, either directly or by augmenting the builder scripts (assuming that's possible). But the work-around would be labor-intensive and not robust to changes by the tool vendors. It would be an ugly hack, in other words.

That work-around would not be portable either. The Ada standard can't address

hardware- or OS-specific initialization, but it can standardize the name for a

routine to do the Ada-specific initialization. Specifically, procedure

adainit initializes the Ada application code and the Ada run-time

library. Similarly, one might need to shut down the Ada code when no further

calls will be made to the exported Ada routines. Procedure adafinal

performs this shut-down functionality. Neither procedure has parameters.

The main function in the other language is intended to import these routines

and manually call them each exactly once. adainit must be called prior

to any calls to the Ada code, and adafinal is to be called after all the

calls to the Ada code.

For example:

#include "stdio.h"

extern int checksum (char *input, int count);

extern void adainit (void);

extern void adafinal (void);

int main (int argc, char *argv[]) {

char * Str = "Hello World!";

int sum;

adainit ();

sum = checksum (Str, strlen (Str));

adafinal ();

printf ("checksum for '%s' is %d", Str, sum);

return 0;

}

In the above, we have an Ada routine to compute a checksum, called by a C main

function. Therefore, we use "extern" to tell the C compiler that the "checksum"

function is defined elsewhere, i.e., in the Ada routine. Likewise, we tell the

compiler that functions adainit and adafinal are defined elsewhere.

The call to adainit is made before the call to any Ada code, thus all

the elaboration code is guaranteed to happen before checksum needs it.

Once the Ada code is not needed, the call to adafinal can be made.

Both adainit and adafinal have no effect after the first

invocation. That means you cannot structure your foreign code to iteratively

call the two routines whenever you want to invoke some Ada code. In practice

you just call them once in the main and be done with it.